Image: Simone Cavadini/Talent & Partner/Chaumet

Image: Simone Cavadini/Talent & Partner/Chaumet

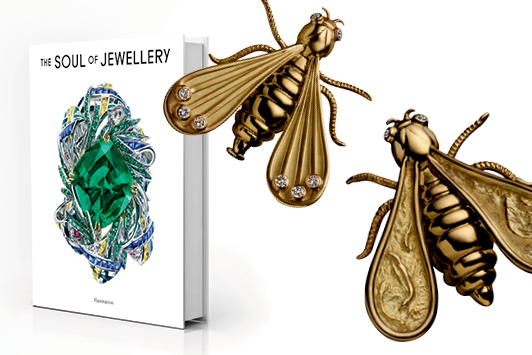

Jewelry is “a work of art, arising from the talent of its creator and the beauty of its stones.” So begins the foreword to The Soul of Jewellery, a new book that goes on to describe its subject as “an object of transformation, of social intercession, and of power that speaks of seduction and adornment,” among many other things.

Casting a wide net, the publisher brought together an eclectic group of contributors whose expertise ranges from science to the arts and who provide thoughtful tangents to the traditional discussion of jewelry’s finer points. Among these contributors are botanist Marc Jeanson, mineralogist Érik Gonthier, artist Joana Vasconcelos, architects Dominique Jakob and Brendan MacFarlane, auctioneer Benoît Repellin, senior curator and Art Deco specialist Évelyne Possémé, composer and pianist Karol Beffa, novelist Carole Martinez, perfumer Frédéric Malle, art historian Charline Coupeau, journalist Virginie Mouzat, French literature specialist Sophie Pelletier, senior curator and Asian-art specialist Amin Jaffer, philosopher Emanuele Coccia, and photographer Julia Hetta. Lavish illustrations from the archives of Parisian jeweler Chaumet complement their words.

Fabulous flora

Starting off the exploration is Jeanson, who sees the “vocabulary of botany” represented in the many natural themes that have featured in jeweled creations through the ages — “from the triumphal crown inspired by laurel leaves and set on a victor’s brow, to the expressive and poetic Camélia bracelet in gold, silver and rubies by JAR 20 years ago, not forgetting the wonderful pieces designed by René Lalique at the turn of the 20th century.” All of these, he says, were “created from a remarkably attentive and rigorous observation of natural flora.”

The beauty of the plant world “and its simple, unsurpassable forms nurture the creative imagination and have inspired countless masterpieces” in a variety of artistic disciplines, he continues, including “Egyptian architecture, medieval millefleur tapestries and manuscripts, splendid Art Nouveau works, Matisse cut-outs, and paintings by Georgia O’Keefe.”

The craftsmanship of fine French jewelry “is no exception,” he says. “The plant-themed designs of jewelers such as Chaumet, Mellerio, JAR and Boucheron are like fascinating, timeless fossils, whose woody, cellulose elements are substituted by the rarest stones and the most precious metals.”

Eminently collectible

The drive to collect these and other extraordinary jewels has enticed all strata of society “in every period,” writes Repellin in his chapter. From monarchs and maharajahs to the courtesans of the late 19th century and Belle Époque, all shared a love of flaunting fine gems. Connoisseurs in the 20th century included “worldly women in high society or from noble, royal or wealthy industrial families” — among them the duchess of Windsor and socialites Daisy Fellowes and Barbara Hutton, who were associated with some of the most well-known jewelers of their day. Then there was the Hollywood set, who assembled their own fine collections. Repellin points to Elizabeth Taylor’s expansive selection of jewels, and to actress Maria Félix, for whom Cartier fashioned several “legendary” crocodile and serpent necklaces.

While jewelry is designed to dazzle when worn, he adds, connoisseurs can appreciate the “intrinsic beauty” that makes a piece a work of art in its own right, “enhanced by its provenance.” When a family collection goes up for sale, it can tell a story illustrating the “styles and fashions as well as the history of the family and its leading members.” As an example, he cites the 2018 auction of the Bourbon-Parma family jewels in Geneva, which encompassed approximately 100 items dating from the 18th century to the mid-20th.

Desire and power

For Coupeau, a distinguishing feature of jewelry is how intensely people want it.

“As an attractive object made of coveted materials, jewelry becomes a source of experience incarnated by desire, fascination and temptation,” writes the art historian. “Although jewelry has changed its form, appearance and meaning down through the ages and across social upheavals, one feeling has remained unchanged: desirability.”

Indeed, she says, “the rarer and more beautiful the jewelry, the more it expresses desire. That is why jewels have fascinated people since the dawn of time. Coveted by men as well as women, jewelry has been a source of countless passions.”

It can also signify great wealth and power, as Jaffer remarks in his section of the book. Many have attributed talismanic meanings to the gemstones in valuable jewels.

“Precious stones represent the most concentrated form of wealth that exists,” says Jaffer. “Throughout history, they have been worn as a conspicuous expression of affluence, and their ownership has been intrinsically linked with power. The amassing and wearing of gemstones are aspects of royalty that are shared across cultures.”

The pursuit of these gems ultimately became a “global race” to fill royal coffers, he recounts. Once the fabled markets of India became known, the desire to own precious stones inspired quests to the country to seek its treasures. In fact, Jaffer says, a jeweler was part of explorer Vasco da Gama’s entourage on his first voyage to the Indies in 1498.

France’s King Louis XIV was one famous jewelry aficionado, wearing diamonds from head to toe to highlight “his position at the center of the universe,” Jaffer says. Catherine the Great excelled in this area as well; by 1792, the Russian regalia included the 189.62-carat Orlov diamond mounted on the imperial scepter. Napoleon, too, “used jewels to express authority and to underline the splendor of his court.” Along with the creations he commissioned for his wives — Joséphine and later Marie-Louise — from court jeweler Marie-Étienne Nitot, his choice of ceremonial jewels included a sword with the 140.64-carat Regent diamond in its hilt, surrounded by 42 other diamonds from the treasury.

Rounding out the book are further musings on jewelry as object — of the earth, of draftsmanship, of artistic value, of fashion, of elevation, and even of dreams, to name just a few of the chapter topics. Beffa’s section explores the parallels between jewelry and music, noting that “necklaces, bracelets, pendant earrings and girandoles jangle as they sparkle,” and pointing to the bejeweled brilliance of opera divas’ costumes. Jakob and MacFarlane write from an architectural standpoint: “Buildings are often compared to human bodies, which makes it only logical to compare ornament on buildings to jewelry.” And as for dreams, Hetta captures the essence of this angle with her expressive photographs.

The Soul of Jewellery was published in October by Flammarion, in collaboration with maison Chaumet.

Article from the Rapaport Magazine - November 2021. To subscribe click here.